Author Archives: Paul Asay

The Butler: Fathers and Sons

Elysium: Heaven on Earth

A Friendly Response to a Friendly Atheist

Christians can no longer hide in a bubble, sheltered from opposing perspectives, and church leaders can’t protect young people from finding information that contradicts traditional beliefs.

|

| An Agape feast from an early Christian catacomb |

|

| Man Reading by Candlelight by Matthias Stom |

Christendom has had a series of revolutions and in each one of them Christianity has died. Christianity has died many times and risen again; for it had a god who knew the way out of the grave. But the first extraordinary fact which marks this history is this: that Europe has been turned upside down over and over again; and that at the end of each of these revolutions the same religion has again been found on top. The Faith is always converting the age, not as an old religion but as a new religion.

The Wolverine: Finding Purpose

For Logan in The Wolverine, that\’s a hard question. The one-time X-Man has seen better days. He\’s still riddled with guilt and despair over the events of X3: The Last Stand, when he was forced to kill his love, Jean Grey. His immortality has become a wearisome burden. Now the guy lives in a cave, away from everything he could love or hate or feel anything about at all.

After his strange encounter with Yashida, Logan meets his beautiful granddaughter, Mariko. And it’s not long before he realizes that lots of folks want her dead. Now, Logan may not be the warmest guy you’ll meet, but he’s always had a thing for protecting people. And so he swings into action, protecting Mariko as best as he can.

After his strange encounter with Yashida, Logan meets his beautiful granddaughter, Mariko. And it’s not long before he realizes that lots of folks want her dead. Now, Logan may not be the warmest guy you’ll meet, but he’s always had a thing for protecting people. And so he swings into action, protecting Mariko as best as he can.The Conjuring: Good Exorcise

To me, this genre deals more overtly with the supernatural than any other genre, it tackles issues of good and evil more than any other genre, it distinguishes and articulates the essence of good and evil better than any other genre, and my feeling is that a lot of Christians are wary of this genre simply because it\’s unpleasant. The genre is not about making you feel good, it is about making you face your fears. And in my experience, that\’s something that a lot of Christians don\’t want to do.

Running on Faith: Forced Rest

Could America Use More Secularism?

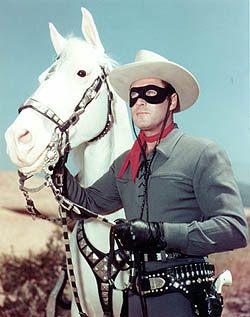

The Stranger Ranger

Cynicism is very easy to write. Cynicism\’s the easiest thing to write. And if you hammer me for two hours about how this character is a symbol of hope, and he will lift us to the sun, and he will inspire us to greatness and he will show us the light … there’s no payoff for that, because in the end, he makes a very cynical decision and we’ve lowered Superman to our level, and that is not what Superman is created for. We don’t need Superman to be more like us. We are supposed to be more like Superman.

Fire and Remember

|

| The cabin, near South Fork |

|

| My son, Colin, and Wendy on the cabin swing, about 20 years ago |

|

| Me on the same swing, about 2008. Colin\’s in the back and my daughter, Emily, is to the right |